This tool has been developed as part of the Inclusive School Communities Project, funded by the National Disability Insurance Agency. The project is led by JFA Purple Orange.

Introduction

This tool assists educators to create an inclusive school culture by providing strategies that respectfully acknowledge the competencies of all students, particularly students with disability. Educators will be encouraged to reflect upon attitudes, beliefs and assumptions of disability that impede viewing students as competent. When educators view students as competent, they will find ways to support students to demonstrate their competency. Presuming incompetence causes irreparable harm. The handout within this tool can form the basis of professional learning.

The term ‘presume competence’ has become part of the philosophical foundation of the social justice movement focused on the dignity of individuals with disabilities. To ‘presume’ means to believe or accept that something is true until proven otherwise. ‘Competence’ refers to the belief that one can think, learn and understand. Another synonym for ‘competence’ that is utilised by the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS), as well as within the legal and policy realm, is the term ‘capacity’. This usage refers to people with disability as citizens who exercise choice and control and contribute to social, economic and political life. Within education, the presumption of competence should be provided to every student, regardless of his or her ability. Presuming competence helps educators to maintain a respectful relationship with students.

The notion of presuming competence is embedded within human rights legislation. Article 12 within the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities1, which informs the Disability Discrimination Act2 and the Disability Standards of Education3, recognises the right of people with disability to enjoy legal capacity 'on an equal basis with others in all aspects of life.’

Ideas

The term 'presume competence' operates similarly as the presumption of innocence in a legal trial where the onus is upon the prosecutor to prove guilt. Presuming competence means you believe that the student in question has potential to develop their thinking, learning, and understanding. Judgments about students’ competence affect every decision about educational placement, programs, communication systems, adjustments to the curriculum, social activities and the future.

Presume Competence and the Least Dangerous Assumption

The term ’presume competence’ was initially coined by Anne Donnellan (1984)4, a well-respected researcher in the field of special education who stated:

...the criterion of least dangerous assumption holds that in the absence of conclusive data, educational decisions should be based on the assumptions which, if incorrect, will have the least dangerous effect on the likelihood that students will be able to function independently as adults. (p. 142).

Donnellan5 proposed that teachers should assume all students, regardless of intellectual ability, are competent and able to learn, and should be provided with every opportunity to learn. If they learn, that is wonderful. If they do not appear to learn after being presented with every opportunity to do so, then the consequences are not as dangerous as the alternative. Providing opportunities is far better than not providing opportunities. Setting high expectations is far better than accepting low expectations. Providing a rich, inclusive learning environment is better than accepting less and discovering when it is too late that this student had capabilities and potential that were missed. The opposite can lead to adverse outcomes for the student such as fewer educational opportunities, inferior literacy instruction and fewer choices in life, particularly as an adult.

The Presumption of Competence and Communication

Communication is closely intertwined with the notion of competence, and this is problematic for students who do not have an effective means of communicating. Communication is viewed by many as a signifier of intelligence6. However, communication is simply the way humans’ display intelligence; it is not necessarily a sign of intelligence. Nearly all activities in the school context are inextricably linked with the act of communication. Students who do not have a means of communicating are unable to show their intelligence. Therefore educators must be careful not to equate lack of speech with intellectual disability. The terms 'high functioning' and 'low functioning' are often used as a label for the degree of speech a student has. These terms are problematic in many ways and are not diagnostic terms. These terms fail to provide information about what students can do. For example, many students who do not use speech are found to have higher cognitive abilities than first realised. They simply need the right tools and support to find their voice7.

The Presumption of Competence and Inclusive Education

The presumption of competence is a foundational concept for inclusive education because it means that every student should be provided with the chance to learn alongside their peers without requiring proof they can learn. Unfortunately, many students with disabilities often need to prove their competence to receive a placement within general education. Thus, placement decisions are usually made on assessments and presumptions, which are flawed, as it is impossible to accurately assess the intelligence of someone who is unable to communicate what they know8.

The presumption of competence is a strengths-based approach that challenges the notion that students with intellectual disabilities belong in segregated settings. It draws on the social model of disability where the barriers to participation are within the environment, not within the student. Therefore, with appropriate adjustments, supported decision-making and access to a robust communication system, students with disability can flourish in inclusive settings.

The Presumption of Competence and Other Learning Theories

Vygotsky’s (1978) Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD)

Vygotsky's theory refers to the difference between what a student can do without help and what they can achieve with support and guidance.9 Using ZPD, goals should be one step out of reach and supports or scaffolds put in place to enable students to reach these goals. The notion of 'presumed competence' along with ZPD means that unless assessment demonstrates otherwise, educators should begin teaching a student at their age level, so they are not underestimated based on our assumptions. However, Vygotsky reminds us to provide enough support, so the student is successful at a given task, but not to overcompensate, so the task is completed without effort. The ZPD approach relies on careful observation and assessment to ensure students are not given too much support or too little. Hence, the elements of the task that are scaffolded are those that the student has not yet mastered. Educators also need to be aware not to infantilise students when simplifying tasks; ensuring tasks are age-appropriate for the student and within their individual ZPD.

Dweck’s (2006) Growth Mindset

The ideology of ‘presume competence’ fits well with Dweck’s concept of growth mindset.10 Dweck (2006) coined the terms 'fixed mindset' and 'growth mindset' to describe the underlying beliefs people have about learning and intelligence. When students believe they can achieve more and that extra effort is the key to that achievement, then they will put in extra time and effort. Growth mindset also applies to teachers regarding their view of their students. If teachers believe that students are competent and capable, they will ensure their teaching is aligned with this belief. However, it is essential to ensure that high expectations are coupled with adequate supports to ensure students can be successful. It is easy to fall into deficit thinking where the lack of success is attributed to the individual's disability rather than removing the barriers to their success.

It is important to note that there are limitations to the presumption of competence and it has been linked to communication practices that are considered to be unreliable and not supported by research, such as facilitated communication.

Actions

Educators’ attitudes and judgments about students’ competence affect every educational decision from student placement to curriculum adjustments. Therefore, to give every student the best chance of success, educators must start from a presumption of competence. We encourage schools to critically examine the ways that presumption of competence is embedded in their pedagogical framework and policies, and in the classroom practices of their educators. Inclusive schools provide regular opportunities for their leaders, teachers, and assistants to identify their values and beliefs and actively dismantle their biases. The following suggestions are a starting point for applying the presumption of competence and other related ideas explained in this tool.

1. Start by understanding your conscious bias and how you view students with disability. Do you have a positive or deficit view of disability? It is when we question our bias that we are open to changing it.

2. Value each student regardless of ability, gender, race, culture, religion and sexuality.

3. Question the language choice and the labels used for students with disability in your context (e.g., the word ‘special’ is considered problematic by the disability community). Check for unintended consequences of language choice and labels.

4. Learn about valued disability identities through exposure to people with lived experience of disability.

5. Recognise and respond to barriers to students with disability achieving educational success.

6. Build an authentic relationship with students where you get to know them as an individual with strengths, passions, and goals.

It is when we have a relationship that we can recognise the subtle, and sometimes not so subtle, behaviours that have meaning.

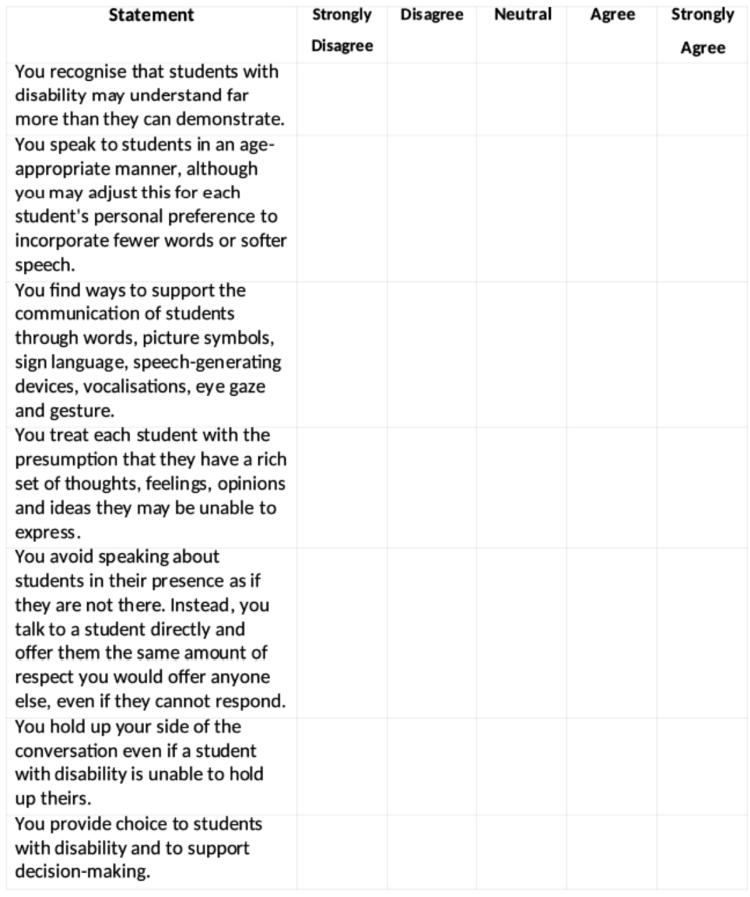

The Presumption of Competence Checklist (on the next page) is a way of developing a critical consciousness of the notion of ‘presumption of competence’. Please read each statement and tick the box that represents your level of agreement. When completed, total each section. If your score falls mainly within the 'agree' or 'strongly agree' section, you have a strong understanding of the presumption of competence. If your score falls within the other areas, it would be helpful to reflect on your values and beliefs regarding the education of students living with disability.

Handout 1: Presumption of Competence Checklist

More Information

Here are links to further reading on the presumption of competence.

Eliminating the Presumed Incompetence Paradigm by Kathie Snow. https://www.disabilityisnatural.com/presume-comp-3.html

Under the Table- The Importance of Presuming Competence by Shelley Moore, a Canadian inclusive educator. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AGptAXTV7m0

Presume Competence by Assistive Ware, a business that makes Augmentative and Alternative Communication products. https://www.assistiveware.com/learn-aac/presume-competence

Five Reasons Why Presuming Competence is a Good Idea by Dr Cheryl Jorgenson, an inclusive educator in the U.S. https://swiftschools.org/talk/five-reasons-why-presuming-competence-is-always-a-good-idea

Acknowledgement

This tool was written by Dr Leanne Longfellow, Director of Inclusive Education Planning and edited by JFA Purple Orange. Leanne presents researched based professional learning to support teachers, assistants, other professionals and parents on inclusive practice https://inclusiveeducationplanning.com.au/

References

1 United Nations (2006). Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, viewed 12th July 2020 https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights- of-persons-with-disabilities.html

2 Australian Government (1992). Disability Discrimination Act 1992, viewed 12th July 2020 https://www.legislation.gov.au/Series/C2004A04426

3 Australian Government (2005). Disability Standards for Education 2005, viewed 12th July 2020 https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/F2005L00767

4 Donnellan, A. M. (1984). The Criterion of the Least Dangerous Assumption. Behavioral Disorders, 9(2), 141–150. https://doi.org/10.1177/019874298400900201

5 Ibid.

6 Marrus, N., & Hall, L. (2017). Intellectual Disability and Language Disorder. Child and adolescent psychiatric clinics of North America, 26(3), 539–554. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2017.03.001

7 O'Byrne, C., & Muldoon, O. T. (2019). The construction of intellectual disability by parents and teachers. Disability & Society, 34(1), 46–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2018.1509769

8 Cologon, K. (2019). Towards inclusive education: A necessary process of transformation. Report written by Dr Kathy Cologon, Macquarie University for Children and Young People with Disability Australia (CYDA)

https://www.cyda.org.au/resources/details/62/towards-inclusive-education-a-necessary-process-of-transformation

9 Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press

10 Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press